Author’s Note

January 24, 2024 | Dan Fichter

Counselors who work on suicide hotlines are gifted with language. Reflecting back a deep impression of someone’s feelings, and fitting words to whatever anticipation or hope that person may be holding onto, is what they do incredibly well.

Greta Opzt and I recently surveyed crisis counselors and asked them to reflect on the state of the 988 system. In response, counselors provided a compelling analysis of the system’s challenges and offered creative and hopeful ideas for a more sustainable and capable 988. They also described the work, itself, in moving terms. One wrote that they feel like a buffer between callers and suicide, and added: “I get to witness the power of the human will to overcome feelings of loneliness, hopelessness, suicidality, and powerlessness.”

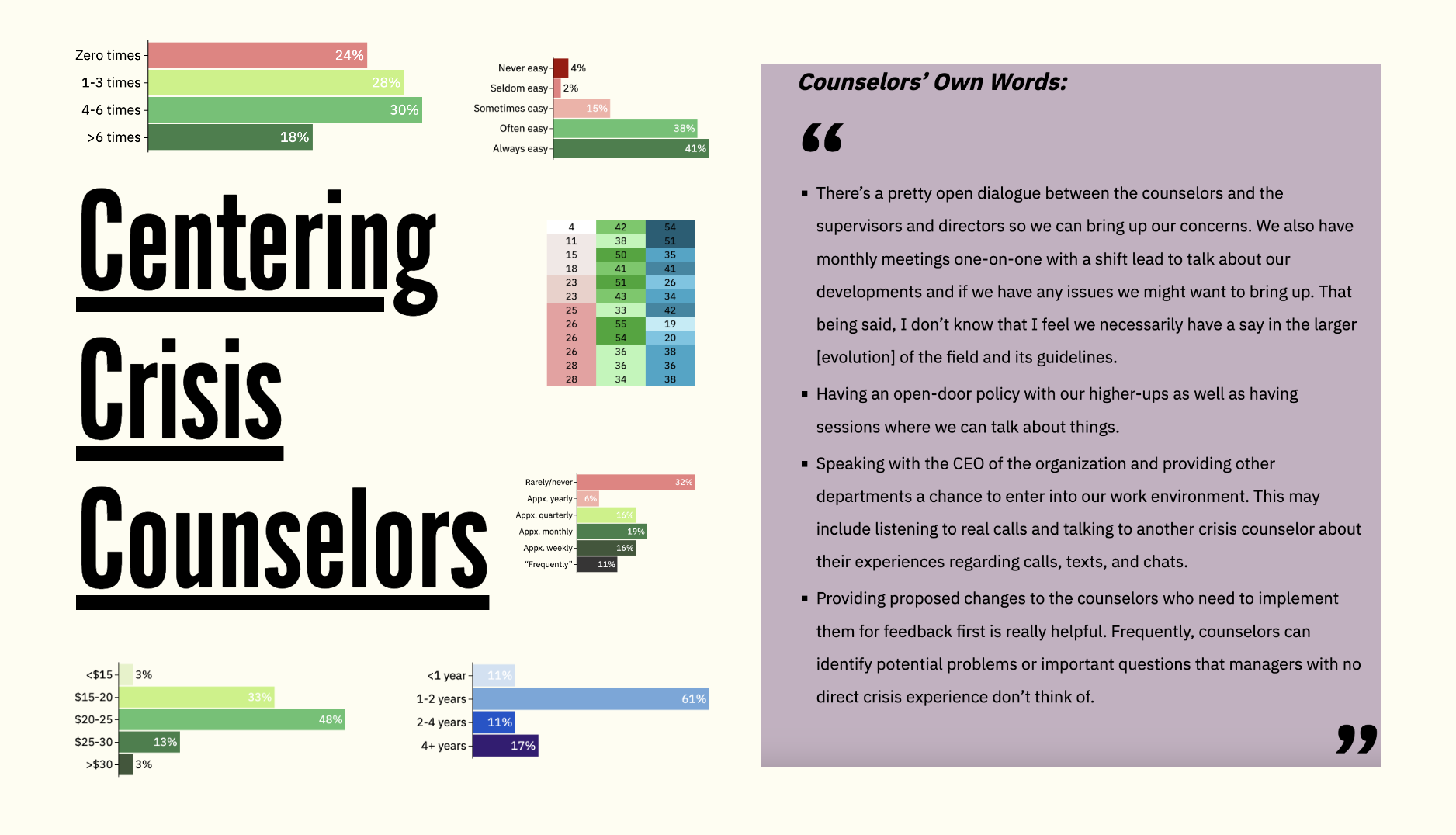

That same 988 counselor also described “living below the poverty line while dealing with the ever-present struggles of compassion fatigue, vicarious trauma, and burnout.” Our system can do more to help the helpers who together answered 2.9 million calls and took over 1.5 million crisis chat and text conversations in 2023. Like EMTs and 911 operators, crisis counselors are underpaid and overstretched. But unlike other categories of first responders, their work has rarely been studied nationally, and they lack a professional association or other organ of voice in the development of their field.

Close to 50 counselors participated in our study, representing experiences at nearly 10% of America’s suicide crisis centers, including many of the largest. Nearly all (96%) said they generally feel able to give callers the care they need. But while many said that their center is staffed so that they can spend as long as they need with callers, others reported pressure to wrap some calls and chats up after 30, 20, or even 15 minutes, just barely long enough to hear why a caller is calling. Texting with multiple people in crisis at once can make shorter time caps feel even more unworkable.

Their training, too, can feel rushed. Many crisis counselors get hired without educational prerequisites, and so their training on the job — often their entire initiation to how suicide prevention works — can last only a few days. At some 988 centers it is much longer: Arizona- and Oklahoma-based Solari told me their trainees listen to at least 20 real calls, and rehearse the skills they are learning in at least six lengthy role-plays. Goodwill of the Finger Lakes follows a similarly thorough training protocol and matches each trainee with multiple experienced mentors. Many centers see direct exposure to what both sides of real crisis calls can sound like as vital to training. But at others, training is dramatically shorter, and trainees never listen to real calls or role-play simulated calls all the way through.

Some counselors wrote that the brevity of their training can feel “downright dangerous”, only sparsely touching on vital topics like anxiety, depression, child abuse, eating disorders, and how to handle abusive calls. With remote work now common, many trainees do not get to hear how experienced counselors sound on calls either in training or while sitting next to them on shift.

At some 988 centers, hearing and discussing difficult calls as a group is central to a weekly or monthly cadence for continuing education. But one counselor shared: “I was there for three years and not once was [an ongoing learning session] held.” A significant number of others also got ongoing training rarely, as badly as they wanted it. One counselor proposed a way to spread the wealth: rather than each build (or struggle to build) continuing education programs of their own, the 200 centers in the 988 network could pool example calls together for use as monthly discussion material.

988 centers might also consider pooling localized resources, including lists of clinics, shelters, and aid agencies that counselors can use to tremendous effect if they have them at their fingertips. They sometimes do not, and some national hotline centers in particular seem to be struggling with this. One counselor wanted to tell callers about non-police mobile crisis teams near them but said: “technically, I’m pretty sure we’re not supposed to do that. We’re supposed just to use the vetted resources on [our] site, none of which are regionally specific.”

Centers should also compare notes on handling unconsented police interventions, which are reported to occur on average under 1% of the time, but which counselors at some 988 centers feel happen too readily. Some counselors are trained in how to tell a caller when they have to intervene without consent, to remove the element of surprise when first responders arrive. But others reported being trained never to say anything to callers about 911 calls in progress, even when they wished they could. This is a striking kind of inconsistency within the 988 system (and, at two 988 centers, inconsistency within a center). Getting consistent here could enable better public messaging about exactly what you should expect if 988 feels a need to send police to find you without your consent, which in turn could help people in many communities feel safer using 988 in the first place.

Only 41% of counselors surveyed felt they could always get a supervisor’s help during a difficult call when they needed it, and nearly a quarter had received no off-shift coaching in the last six months. Many found written feedback on randomly-selected calls they took to be generic and unhelpful; others got to steer live coaching sessions to areas they wanted help in. One counselor brilliantly suggested solving for the shortage of supervisors, coaches, and reviewers by letting experienced counselors serve in those very capacities for part of the week, while answering crisis calls the rest of the week. (This could also ease burnout from being on shift, and might supercharge the circulation of knowledge within crisis centers.)

Crisis counselors rarely get a chance to attend 988 conferences, sit on panels, advise on studies, or write about their experiences. They are not seen, yet, as a profession. The counselor who said they marvel at the power of the human will after hard shifts also wrote on the survey: “I have never felt heard before now.”

988 centers are working in remarkable isolation from one another, and the system is not always centering the insights of its frontline staff. We let acutely suicidal callers across the country follow these counselors’ lead through their scariest moments. We should not be afraid to follow their lead on policy and research questions that will shape their field. 988 centers might take a page from what their counselors tell callers every day: sharing what’s going on in a hard situation can be an important start toward seeing hope.